Blind Architect Chris Downey Designs Buildings Like No Other

Could you design a building blind, using only touch? Blind architect Chris Downey does – & the results are amazing.

Could you design a building blind, using only touch? Architect Chris Downey does. In 2008, after the removal of a benign brain tumour, Downey lost his sight. Rather than letting it end his career, Downey tells how he learned to rely on other senses… and discovered a whole new approach to architecture.

Interview by William Sigsworth

Though incredibly important to an architect, touch is not a sense that we have always appreciated. In fact, a criticism often levelled at our profession is that we have become so visually orientated.

With all the screens we now work with, sight is easy and quick – it gives us the ability to see at a distance and we don’t even have to be there in person. But in reality, the end product is not on a screen, it’s not a representation; it’s a real thing in space and time. And a big part of that is the full range of sensations that you get only by physically experiencing a building.

The Sense of Touch

With sight, the reaction is, ‘Oh, that looks good,’ as opposed to, ‘That feels good.’ Touch is something subtler, as it might not come to mind as quickly. For most people, 80 per cent of the environmental sensory experience is visual, leaving just 20 per cent for everything else.

Our sense of taste doesn’t have a whole lot to do with architecture, but the senses of touch, smell and hearing are so important.

There are things we architects know are going to get touched, such as a doorknob or a front door. Think of those haptic moments in life. One we often experience is a handshake. Without sight, the first thing I have to work with when I meet someone is their voice. You can tell a lot: how tall they are, based on where the voice is coming from (as long as you understand the level of the ground – are they on an incline?).

You also get a glimpse into a person’s personality from their speech patterns. But it all happens so quickly as, without sight, you have to focus so much more on it, while still listening to what they say.

Then you have the handshake: by its intensity and its length, you can almost sense the sincerity of the grip. The same is true of a front door. That first, immediate, impactful experience of a building is the grip of the front-door handle (unless it has an automatic opener).

I also really like to think about the sequence of things as you move through a building, what you know you are likely to physically engage with, and then design that object for each moment in the sequence of experience. Touch, then, may or may not be immediately understood by the visitors to the building, but it contributes to the experience in an all-encompassing way.

Making the design process a sensory experience

In architecture, we use drawings to design our work. We may use models, too, but they’re also about visualising the space, rather than the surfaces – seldom are they designed to be explored through touch. In my work, however, touch is a vital part of the design process.

I worked on a project in San Francisco called the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired. We were designing the staircase to link the three floors of their space. That stairwell was the heart of everything, the unifying element of the three separate floors – without it, you’d have to leave the space to use the elevators in the surrounding building’s common area. The staircase was very important, as was the experience people would have when they used it.

While I was designing the handrail, I remembered a past visit to a museum. Going down to a lower gallery, I’d found the first step with my cane and reached for the handrail. The minute my hand took it, I was stopped in my tracks. It was unlike any handrail I’d ever felt, fitting the hand incredibly well. I had to take a photograph of it.

When we were designing the staircase for the LightHouse, we studied that photograph. At first, we created drawings. I would sketch the designs, and then the architects I was working with would draw it on the computer, and finally I would print their drawings to work with.

But I realised that there was something wrong with the process: we were doing it all visually. We couldn’t grip these drawings, we couldn’t experience them. So, instead, we created a 3D print of all the sections of the handrail we were exploring, which allowed us to actually grip it ourselves. It really transformed the process into one appropriate for the sensory experience it was being tailored to.

A deeper level of understanding through touch

Thanks to the tools I use in my design, I can feel the drawing. For architects, the mind plays an important part in visual design – you’re an active viewer, a critical viewer, so your mind is hard at work, thinking through each condition, how it fits into the overall experience and what you’re trying to achieve.

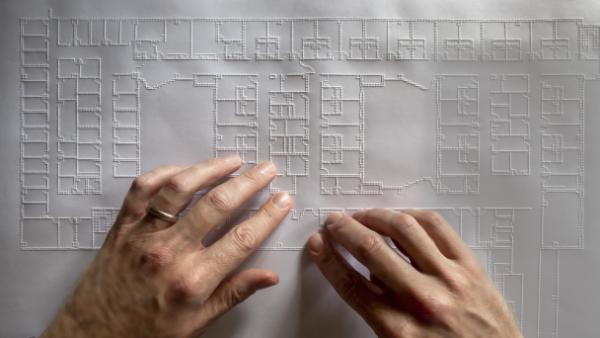

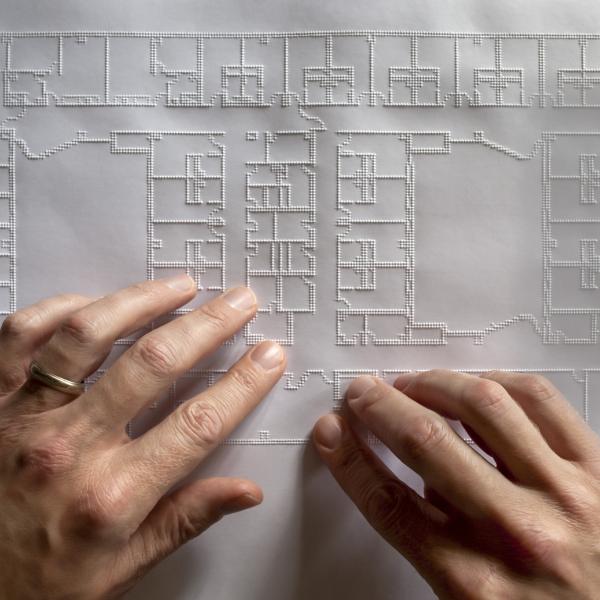

“Reading a plan through touch is very different from looking at it visually, and in some ways more difficult”

My tactile perspective makes everything so much more immediate. Reading a plan through touch is very different from looking at it visually, and in some ways more difficult: you don’t see the whole thing immediately and then understand the detail; you find the detail first and then have to build out to the whole.

It can take a while to figure it out, but once you do, once you have the lie of the land, you can really work with it – because you’re in the space. It’s like the parable of the group of blind men who have never seen an elephant and are each touching a different part. Each man conceives of the elephant in a different way, based on their limited, subjective experience – the one feeling the animal’s trunk has a very different mental picture from the one who is feeling the flank.

As I work with a design over time, my understanding gets embellished with all the surfaces that define a space: the floor, the walls, the ceilings, the windows, the lights, even the colour, how the light comes to the space – a lot of the things we think about visually.

Having had sight for 45 years, I can still visualise the space; it’s just a matter of engaging in it intellectually as I, with my fingertips in the space, review, study and move through it.

An architectural drawing can be as detached as sight. If we’re just looking at it, we tend to look at it for its compositional value: ‘It’s a good composition, great job! You can go home now.’ Whereas with a sense of touch, and your mind needing to be active in thinking through all those things, it takes you to a deeper level of understanding what it would be like to be in that space.

Designs that feel bad to the touch

If not done well, the wrong sense of touch in architecture can be hugely detrimental. It can go from, ‘It looks good,’ to, ‘Oh my God, this thing feels horrible.’ For example, something often done is a simple steel bar handrail – it might look really crisp and really good in a drawing, but the minute you try to walk down the stair holding onto that handrail, you notice what wasn’t considered, such as the edges and that it’s not comfortable to grip.

It changes your perception of the building. And if you don’t have sight, and that’s the only thing you experience, it doesn’t leave you with a good impression of the building – whether you’re conscious of it or not.

And then there are the surrounding textures. Something I never thought about when sighted and working as an architect was the wall surface behind the handrail. One of the principles of universal design is tolerance for error: the appreciation that not everyone uses things with the same level of precision or dexterity.

I was in a convention centre once, which had a handrail attached to a very rough wall. When I ran my knuckles across the wall, it felt like running your fingers across a cheese grater. It may have looked very nice, but it didn’t support that notion of imprecision or tolerance for error.

It’s short-sighted, if you’ll excuse the pun, not to anticipate that people may accidentally hit an area around a tactile surface. And the sense of touch is not just based on what you feel with your hand – it’s about your whole body. After all, we’ve all experienced good benches and bad benches

A building design should always be considered as a tactile experience as well as a visual one. I need to anticipate the areas that get touched intentionally or accidentally.

Tactile architecture: The tools of the trade

1. Wax sticks

I use these where I can feel the drawing underneath that I’m working on. It’s like I’m looking at it through tracing paper and drawing on top, only everything is tactile.

2. 3D-printed models

We did a 3D print of all the sections we were exploring for a handrail, and then we were able to actually grip it ourselves – and have the client work with it – to narrow down the things we liked. Then we kept evolving the design based on how it fitted the hand, not how it looked visually.

3. Embossing printer

I take drawings people see and turn them into PDFs – they look like normal drawings on the computer screen, but my printer converts all the lines to a tactile experience, so I can ‘read’ them.

Photography: © Don Fogg, © Don Fogg/Mark Cavagnero Associates Architects, © Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects/Transbay Joint Powers Authority, Fullmetal2887

This article is taken from the Reach Out and Touch Magazine

published as a partnership between Sappi Europe and John Brown.