The Sense of Touch – Its Origins, Evolution and Purpose

A neurobiologist explains how our bodies, especially our hands, have adapted to makes sense of the things we hold and feel.

Since our earliest prehistoric ancestors, touch has been central to our survival and reproduction. Writer and neurobiologist Dr Liam Drew explores how our bodies have evolved to tell us more than we realise.

Touch is our most intimate sense. Sight, smell and hearing evolved to understand the world at a distance, but touch, like taste, analyses objects in direct contact with our body.

What you touch is likely to have a direct bearing on survival or reproduction. It might be predator, prey or parasite; parent, lover or child; shelter or hazard; tool or food; the ground that you walk on or the branch from which you seek to swing. It is also the first sense to develop, with some foetuses responding to touch in the womb after just eight weeks.

You’ve got some nerve(s)

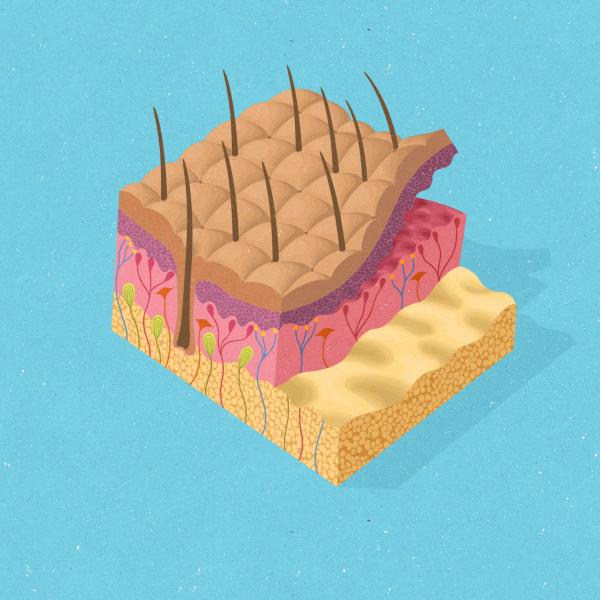

Our bodies are designed to ensure that touch is inherent to everything we do. Regions of our brain and spinal cord are dedicated to processing the information gathered by touch, while the nerves that run through our flesh to the surface, lying just beneath the skin, convert external pressure and energy into a biological signal that signifies a sensation.

"Evolution created a touch system composed of different sensors and receptors, which together detect the qualities of what is touching our body and what our body is touching – its weight, temperature and texture – so that we can deduce what we need to know."

Experiencing pain and pleasure

Curiously, we experience pain through the prism of whatever stimulus evokes it and the context in which it occurs. In a healthy body, quite severe force is needed to cause pain and, even then, if we are distracted we may not feel it immediately. For example, if you’ve ever played a high-contact sport, you may only become aware of the painful impact of a challenge a few hours after a match, as you were too focused on competing at the time.

Conversely, a bruise on a body that is recovering from a severe injury, even when only lightly brushed, can spark a rush of pain.

Experiencing pleasure through touch, meanwhile, has its own mental pathways. The delight an animal or human experiences from a gentle caress might be automatically triggered by the nerves that are stimulated, or it might derive from the psychosocial context of the interaction.

The way you make me feel

In humans, touch is processed by two strips of cerebral cortex, the somatosensory cortex, running down either side of the brain, roughly from the crown to just above each ear. Neurobiologists have mapped how much of this is devoted to each part of the body and it’s by no means equal.

If you were to draw a human figure whose body parts were scaled to reflect the amount of the cortex that is devoted to each region of the body, you would have a diminutive trunk, limbs and feet, a moderately sized head, and massive lips, tongue and hands.

The mouth and how we use it

For most of our biological forerunners, the mouth was an essential interface between themselves and the world. Survival was often based on what was and was not edible. We have retained this ability to discriminate the textures and physical qualities of what we eat in minute detail – what a sommelier might call ‘mouthfeel’.

The development of our hands

The giant hands make sense. But this is a more recent evolutionary innovation. To discover the history of their development, we must trace a path through the primate family tree.

The first primates – who, fossils tell us, lived at least 55 million years ago – scuttled up trees on four regular mammal-grade legs. But through evolution, some of these animals developed feet more capable of grasping branches: their big toes rotated away from the others; claws were replaced with nails; and digits developed touch pads, ridged like fingerprints, to facilitate the sense of touch.

Front and rear feet became progressively more distinct from each other as primates shifted the way they walked towards a more upright, rear-leg-dominated process.

Now, humans possess these elaborate devices with which you are scrolling through this feature.

What touch tells us

Our quiet, often under-appreciated, enriching sense of touch serves many functions – discriminative, exploratory, emotive, sexual and social. And where it is richest, in our hands, we see it most clearly as a sense that has emerged from an animal’s way of life.

Thanks to the density and diversity of the sensory receptors we possess and the brain power that drives them, touch is crucial in helping us navigate our world.